This Research-Creation project led to the development of a manifesto and an exhibition that propose a reflection on the future life of objects, establishing a parallel between a scientific research lab studying DNA. All organisms on earth encode their molecular sources in an instruction manual for life called dioxyribonucleic acid or DNA. Since DNA can be found in all the genetic data that governs the development of living beings, can we imagine a future world where even manufactured objects encode their own genetic information? This site describes an overview of the DNA exposition, which proposes an idealist, yet critical vision of the future of objects, where the visitor is invited to manipulate interactive objects or to play the role of a scientific researcher observing the internal organs of an object with 3D scanners and X-Rays.

In the future, objects will

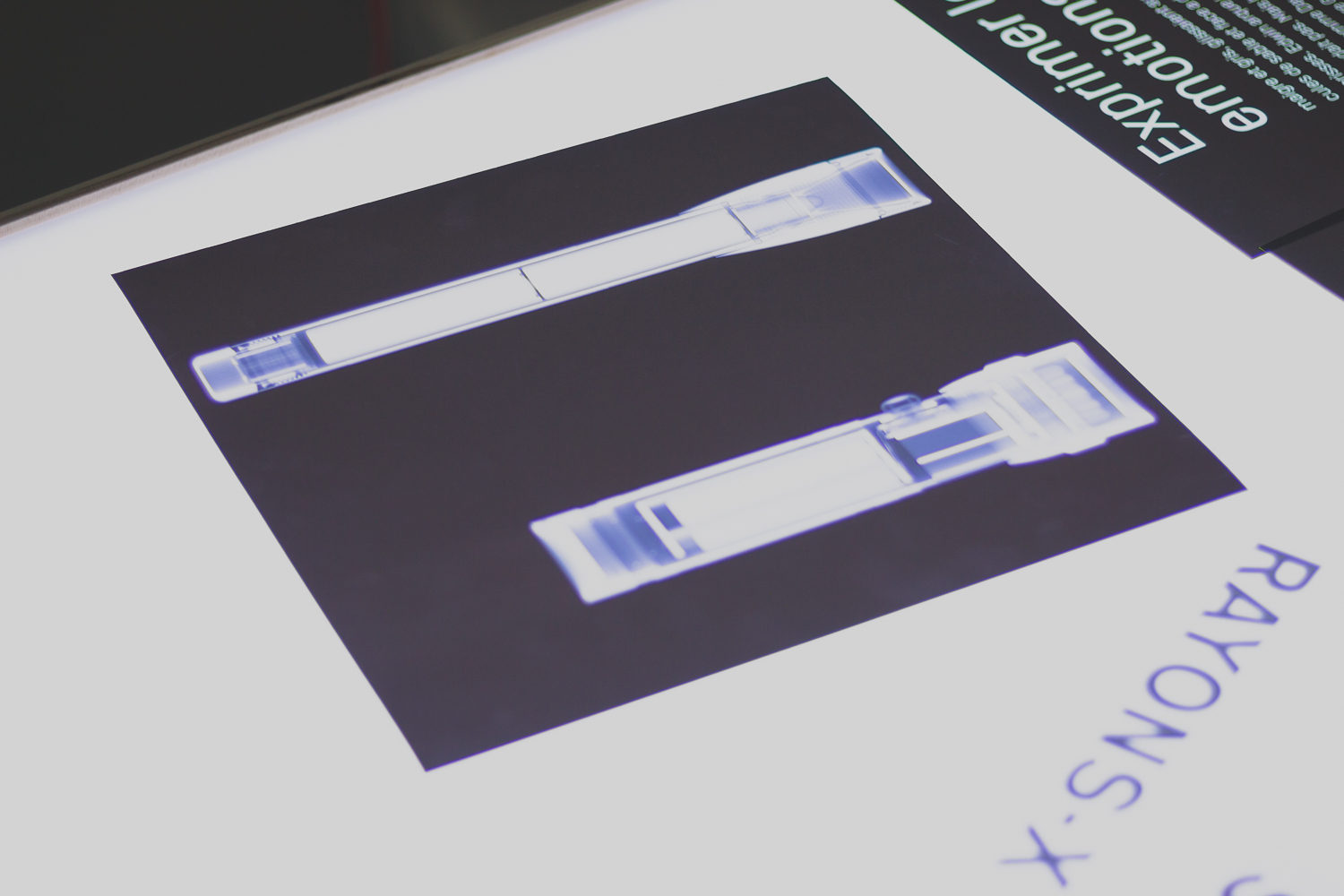

reveal their Anatomy

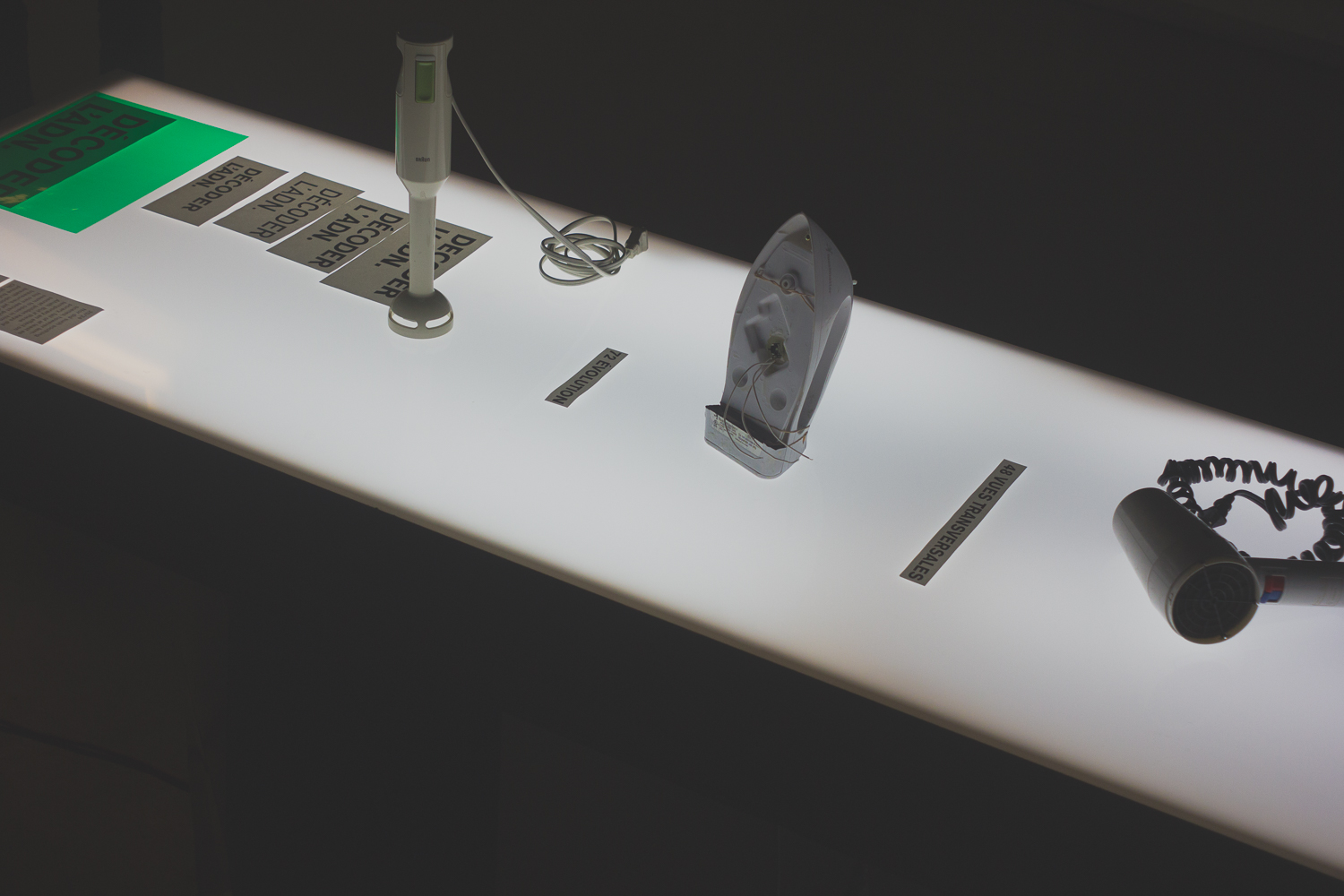

At the moment, most products are designed as closed shells, revealing nothing of the materials from which they are composed. They are assembled in such a way that opening or disassembly is very difficult, and repair impossible. In the future, objects will lend themselves to disassembly and will freely display their “anatomy”, that is the materials from which they are made, much like the ingredients listed on food packaging. It will then be possible to know if a product contains toxic materials or if has been designed to fail after an abnormally short lifespan. This module offers several ways of displaying the hidden dimensions of objects in order to discover what is hiding under their outer shells.

In the future, objects will

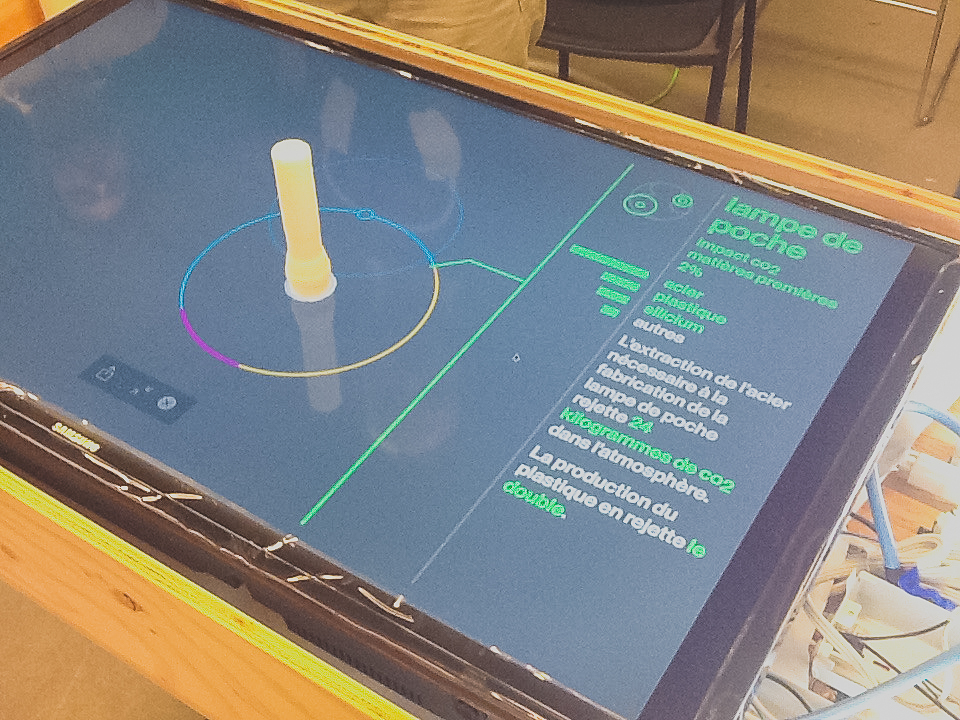

declare their Impacts

Today, products are sold with an instruction manual and limited guarantees, but the environmental impacts resulting from their fabrication are not declared. In the future, users will be informed of the environmental footprint left by the products they consume. Starting from the extraction of natural resources, each step leading to the manufacture of an object has an effect on the quality of air, water and earth. To this, must be added the energy consumed by the transformation of these resources into usable materials and by air, ground and maritime transportation. This module will help you visualize, on a 3D representation of the Earth, the environmental impacts caused by an object as common as a kettle. Which of these two kettles has more of an impact on our planet’s resources : a stovetop glass kettle or a plastic plug-in model?

In the future, objects will

tell their story

Presently, objects that have become obsolete or that have broken down are simply thrown away and find their way into land fill sites, as though they no longer had any value. Each object, however, has a story to tell, recounting how it was acquired to fill a need or to be offered as a gift for a loved one. In a way, the object’s course has followed alongside the life of a person or a family, as a travelling companion and a witness to many of life’s dramas, and has thus accumulated memories worth sharing. In the future, we will be able to read the memories of the objects of our surroundings. This will heighten our perception of their worth and constitute a powerful incentive to care for them and prolong their lifespans rather than discard like worthless junk.

In the future, objects will

express their emotions

Some designers have proposed the development of attachment to objects as an effective strategy for prolonging their lifespan. Is it possible to share an emotional relationship with an object? Can an object sense that it is well treated and appreciated? In the future, the objects of our everyday lives will foster the creation of stronger bonds of attachment with us, which will lead to a more significant and sustainable relationship with our material possessions. Emotional bonding will encourage us to respect objects, to take better care of them and to seek to keep them longer. How will such sentiments express themselves? In this module, through audio and tactile interactions, you will discover a number of objects that have personality and character.

In the future, objects will

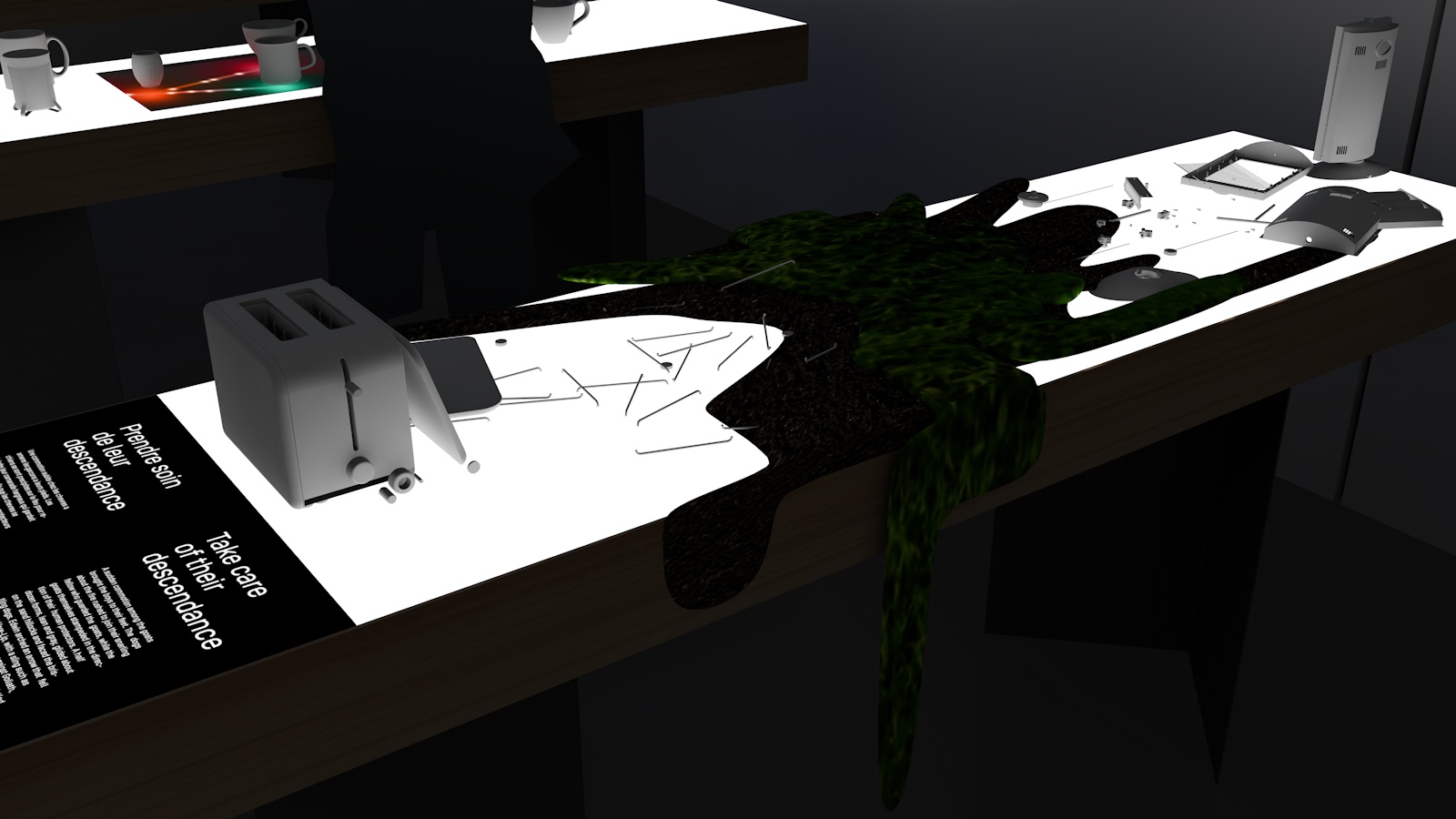

care for their descendants

It seems today that there is no clear strategy to deal with the end of life of objects. Repair is often more costly than replacement and technical obsolescence frequently renders objects prematurely useless. The only alternative becomes the trash bin. Would it not be more reasonable to recognize the value of the natural resources of which objects are composed, rather than throwing them into the trash? In all of history, humans have elaborated rituals of mourning to deal with death. Most individuals seek to care for their descendants by donating their organs and by leaving an inheritance to their children. Why should it be any different with objects? In the future, we will develop strategies for the re-utilisation of objects’ component parts, as well as for the recycling of materials and composting of all organic matters.

In the future, objects will

communicate with each other

The next step in the digital revolution is interconnected objects, defined as “the internet of things”. Objects will acquire the capacity of storing data and sharing information with each other. In the future, we will have the ability of remotely consulting an inventory of the contents of our fridge, we will have access to usage statistics on every electric appliance in our home as well as information specifying the energy consumption of each item. Our shirt will monitor our pulse, evaluate our level of stress and send this information to our car so that it can activate the appropriate driver assist modules. Each of our possessions will be geolocated and its operation remotely tracked. In a world where objects accumulate data and communicate personal information amongst each other, should we be wary of the potential menace that this represents to the privacy of our lives?

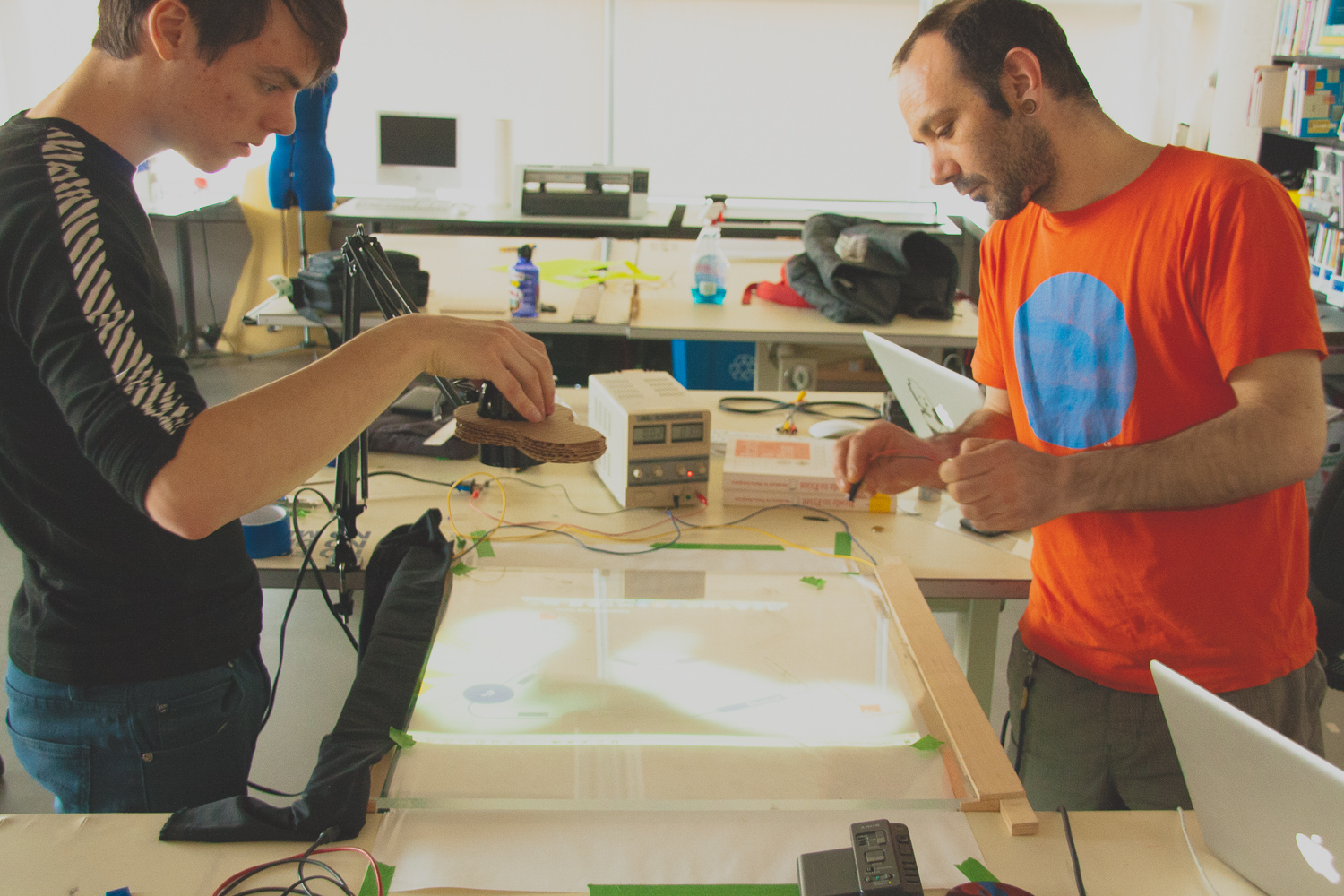

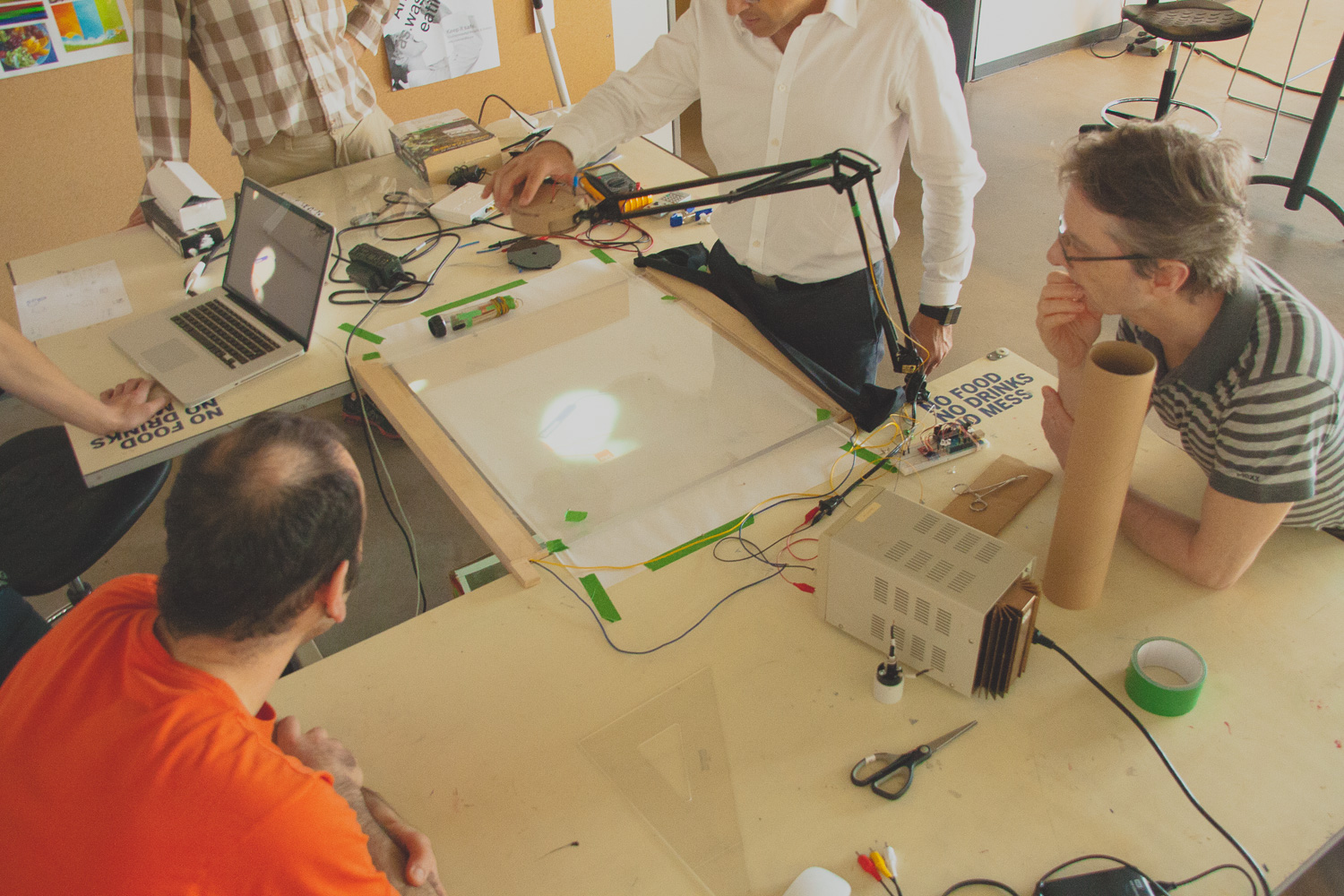

Project DNA

Research & Creation

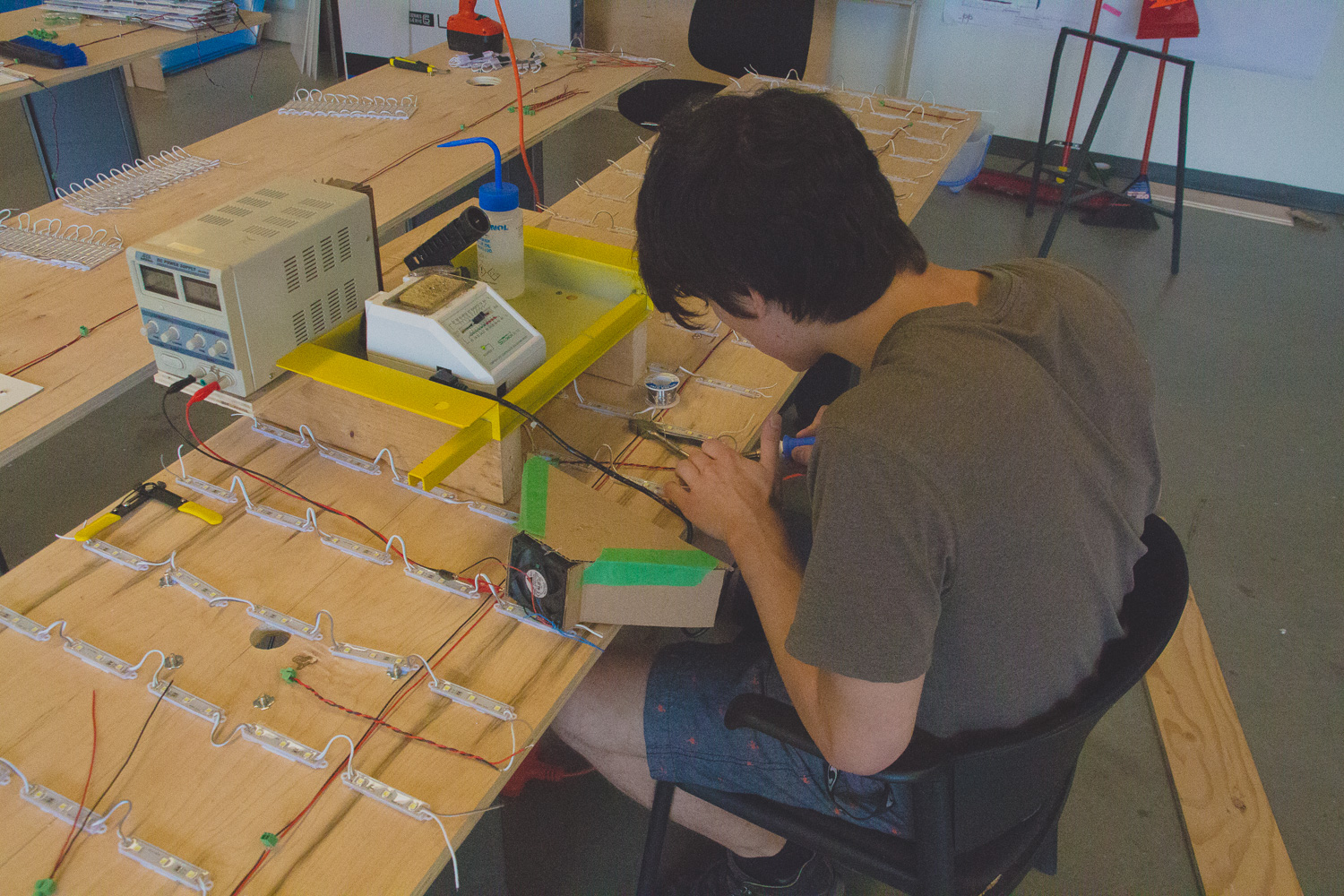

Take a look at the team's work in our Hexagram lab at Concordia University →

ADN

La vie future des objets

Novembre 2016. Gallerie FOFA, Université Concordia EV